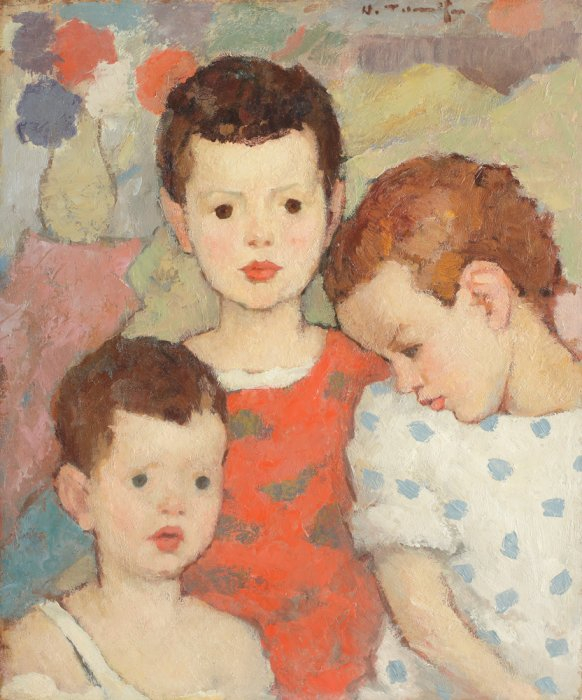

45. Child in Red [1925-1927]

-

Nicolae Tonitza

lot.estimate:

30.000,00 EUR

- 50.000,00 EUR

lot.sold:

55.000,00 EUR

- medium

- oil on cardboard

- description

- The main source of creative inspiration will be his three children. He manages, through an exercise that starts with the birth of his first child and continues throughout the maturation of all his children, to capture a whole carousel of ages and the entire emotional tumult that covers each maturation period separately. In Tonitza's art, the children appear, as he himself stated, "with their charming inexperience, with their harmonious disorder, with their winged indiscipline". He pays special attention to the subject starting in 1924, when he begins to focus more on making a meditative incursion into the theme of childhood. His portraits of children bring him success, a big series of custom orders, and cements his place in Romanian art history. Among his little female muses, we find Catrina and Irina, his daughters; Nineta, his niece; Katiusha the lippovan, or "just a little girl" (often caught sitting, reading, or playing). He does not stop at autochthonous inspiration, but fills his canvases with Dutch, Tatar, Russian, or Italian girls. Sometimes, the title proposed by the artist indicates the profession of the parent of the painted child: "The Clown's Daughter", "The Forester's Daughter", "Magnate's Girl" or "The Florist's Boy" are just a few examples. Other times, it indicates the social status of the model through representation and naming. Preschool age is largely covered by female portraits. Tonitza gives his little muses various decorative elements: bows, bonnets, kerchiefs, or dresses, which he studies carefully and detailed in his works. Most of his portraits include a single face. The artist focuses mainly on a single human figure and allocates enough time to capture both the physiognomy and the whole psychology of the model represented. In the eyes of his muses, Tonitza hides a whole universe and reflects fairytale brilliance. He paints faces devoid of expressiveness, whose mute monologue is entirely nestled in the gaze. He captures eyes that are overflowing with nostalgic innocence, or eyes looking with melancholy and candour. He presents the face as a microcosm on which he intervenes, when necessary, with specific details and protective lucidity. Most of the time, as Barbu Brezianu noted, Tonitza superimposes two or three unblended shades (black over grey or blue; brown over green), thus reaching the final result - "angels with eyes dilated by azure", as Perpessicius observed.

- bio

- ȘORBAN, Raoul, "Tonitza", Meridiane Publishing House, Bucharest, 1973. BREZIANU, Barbu, "N. N. Tonitza", Meridiane Publishing House, Bucharest, 1986. PĂULEANU, Doina, "Tonitza", Official Monitor, Bucharest, 2014.

- dimensions

-

- width: 31 cm

- height: 38.5 cm

- dating

- 1925-1927

- provenance

- composer Anatol Vieru's collection